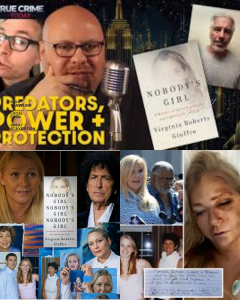

Virginia Giuffre was sixteen when Ghislaine Maxwell glided in with a smile that felt like sunlight and a promise that sounded like rescue. In Nobody’s Girl, Giuffre recalls the exact moment charm turned lethal: Maxwell praising her posture, offering spa tips, then sliding the trap shut with “You’re special—come meet my friend.” What followed wasn’t recruitment; it was mentorship turned monstrous, every compliment a chain. The book peels back the polish to reveal Maxwell orchestrating, participating, normalizing—until one sentence lands like a blade: “She taught me how to please them so well I forgot I was the one being broken.” The mask is off; the mirror is up.

Virginia Giuffre was sixteen when Ghislaine Maxwell glided into her life—a vision of poise, charm, and false warmth. In Nobody’s Girl, Giuffre remembers the moment not as an explosion but as a quiet shift, the kind that feels safe until it isn’t. Maxwell’s entrance was calculated to disarm: a smile like sunlight, a voice that soothed, a hand on the shoulder that suggested care. She praised Virginia’s posture, offered spa tips, talked about opportunity and travel. And then, with surgical precision, came the invitation that would change everything: “You’re special—come meet my friend.”

That was the moment, Giuffre writes, when charm turned lethal.

The genius—and the evil—of Ghislaine Maxwell lay not in overt cruelty, but in the way she made exploitation feel like belonging. Nobody’s Girl reveals this process with haunting clarity. Maxwell didn’t lure Virginia with threats or force; she lured her with approval. She didn’t recruit; she cultivated. What began as mentorship soon turned monstrous. Every compliment became a leash, every gesture a test of loyalty, every soft-spoken assurance another knot in the invisible net.

Giuffre’s prose is unflinching but never indulgent. She writes as someone reclaiming power through truth, not revenge. The horror, as she tells it, is not in the violence itself but in how normal it all seemed at first. Maxwell weaponized trust, disguising predation as mentorship and transforming affection into control. The girl who thought she’d found a protector was instead being shaped into prey.

“She taught me how to please them so well I forgot I was the one being broken.”

That sentence cuts like a blade—and Nobody’s Girl gives it the silence it deserves. It encapsulates everything about Maxwell’s role: the psychological precision, the manipulation of innocence, the way she blurred the boundaries between care and control until Virginia couldn’t tell the difference. The grooming wasn’t an accident. It was an education in submission, wrapped in the language of empowerment.

Giuffre refuses to portray Maxwell as a mere accomplice to Epstein’s crimes. She presents her as a central architect—an enabler who understood how to convert social grace into psychological control. Through Giuffre’s eyes, Maxwell’s glamour rots into something grotesque: the manicured nails that signaled status, the perfect smile that masked complicity, the effortless confidence that hid a hollow moral core.

But the book isn’t only about Ghislaine Maxwell. It’s about the culture that allowed her to operate with impunity. Giuffre’s story forces readers to confront a truth more uncomfortable than any single act of abuse: predators like Maxwell and Epstein thrive not because they are clever, but because society rewards their type. Wealth, elegance, and connection make the monstrous look sophisticated. When someone like Maxwell walks into a room, people don’t see danger—they see pedigree.

In dissecting this illusion, Giuffre exposes the machinery of privilege that kept her silent for years. Institutions looked away because the perpetrators looked “respectable.” The justice system stumbled because the victims looked disposable. In the world Maxwell and Epstein inhabited, morality was negotiable—as long as the money kept moving and the smiles stayed polished.

What makes Nobody’s Girl extraordinary is not its recounting of trauma, but its reclamation of narrative. Giuffre writes with clarity that burns, stripping away layers of myth to reveal a truth so stark it can’t be unseen: evil rarely announces itself. It arrives well-dressed, articulate, and smiling. It tells you you’re special. It tells you you’re chosen.

When the final pages close, the reader isn’t left with pity but with fury—and recognition. Maxwell’s mask may be off, but her reflection lingers in every system that protects power over people.

Giuffre’s memoir is a mirror held up to that world. And when you look into it, you see not just her story, but ours—the complicity we ignore, the predators we admire, the silences we justify.

Because the truth is never as distant as we’d like to believe. Sometimes it walks into the room smiling, and calls itself a friend.

Leave a Reply