Art, Conspiracy, and Censorship: How a Bronze Figure in Beijing’s 798 District Fuels Ongoing Debate Over Actor Yu Menglong’s Death

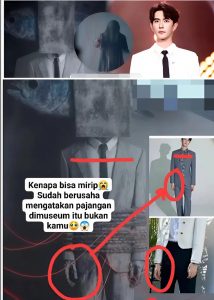

Beijing — Beijing’s 798 Art District, a symbol of China’s contemporary cultural renaissance, has unexpectedly become entangled in a macabre online storm surrounding the death of actor Yu Menglong. Viral posts since October 2025 feature stark visual juxtapositions: a bronze male sculpture with an unnaturally angled neck and slack limbs placed beside purported last-known images of Yu, who died on September 11, 2025, in what authorities deemed an accidental high-rise fall.

The sculpture, exhibited in one of the district’s modern galleries (with ties speculated to venues like Qihao Art Museum), has drawn scrutiny for its hyper-realistic detail. An AI-assisted promotional clip, briefly shared by the institution before removal, showcased the work’s lifelike anatomy, leading netizens to declare the resemblance “chillingly perfect.” Discussions exploded on Weibo and overseas platforms, with users asking whether the piece is provocative modern art, a dark homage, or inadvertent evidence of a crime scene.

Yu Menglong, known for roles in period dramas, was found dead at the Sunshine Upper East complex. Police concluded intoxication played a role, but the rapid case closure — without public forensic details — sparked immediate doubts. The controversy has since layered on broader allegations: secret captivity, torture, and even postmortem body use in art exhibits, echoing rumors about preserved remains or human tissue displays in 798 galleries.

These claims fit a pattern of conspiracy narratives that have proliferated amid heavy online censorship. In the weeks following Yu’s death, Chinese platforms systematically purged content, banning searches for key terms and suspending accounts. International media and diaspora networks have kept the story alive, with global petitions and protests (including in Times Square) calling for justice. Some theorists connect the sculpture to alleged elite involvement, citing the district’s government-linked operators and its cultural prestige.

Contemporary art in 798 often engages with taboo subjects — death, surveillance, bodily autonomy — through figurative works that challenge viewers. Sculptors frequently employ realism to provoke reflection on societal issues. Yet the absence of official responses from galleries has allowed speculation to flourish unchecked.

Observers note that such viral phenomena reveal more about China’s information ecosystem than the artwork itself. In a context where direct inquiry is stifled, symbolic interpretations fill the void. The bronze figure, whether intentional or coincidental, has become a proxy for unresolved grief and demands for accountability.

As 2026 progresses, the debate shows no signs of abating. Without transparent investigation or artistic clarification, the sculpture remains a focal point for those seeking answers in Yu Menglong’s tragic story — a reminder that in censored spaces, even metal can whisper accusations.

Leave a Reply