Public Opinion as Executioner: Phạm Thế Kỷ and the Unresolved Shadow of Yu Menglong

China’s annual “Good People” list is one of the country’s most symbolic honors. It celebrates ordinary citizens and public figures who represent moral integrity: traffic police who risked their lives to save strangers, aging Korean War veterans who quietly endured decades of hardship, everyday people who performed selfless acts without seeking recognition. The list is meant to inspire, to remind society of what goodness looks like in practice.

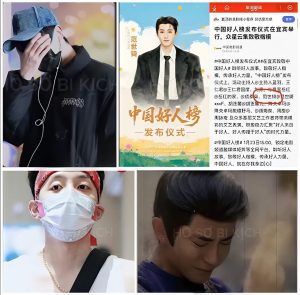

This year, however, the list became a lightning rod for outrage when Phạm Thế Kỷ — a mid-tier singer who first gained recognition through talent competitions and television appearances — appeared as a nominee. Within minutes of the leak, Chinese social media platforms exploded. Millions of users flooded comment sections, reposted old screenshots, and resurrected the name that has haunted Phạm Thế Kỷ for months: Yu Menglong.

Yu Menglong died in September 2025 under circumstances that remain emotionally charged but legally closed. Authorities conducted an investigation and concluded there was no criminal liability. No charges were filed. The case was officially closed. Yet for a significant portion of the online public, closure never arrived. Suspicion, grief, and unresolved anger continued to simmer — and when Phạm Thế Kỷ’s name surfaced on the “Good People” list, that anger erupted into a full-scale digital firestorm.

The backlash was immediate, coordinated, and merciless. Hashtags trended within hours. Old audio clips, screenshots, and unverified rumors were recirculated at lightning speed. Netizens branded Phạm Thế Kỷ everything from “morally bankrupt” to “the real criminal of the century.” The pressure became so intense that the organizing committee removed his name from the list before any formal evaluation, public announcement, or award ceremony could take place. He was erased — not by a court, not by investigators, but by collective online fury.

This episode is far more than a celebrity scandal. It is one of the clearest recent examples of digital mob justice in action. No courtroom. No cross-examination. No opportunity to present evidence or mount a defense. Only volume, emotion, and virality. Phạm Thế Kỷ was not convicted under the law; he was convicted in the court of public opinion. Within days, his scheduled concerts were canceled, television appearances were pulled, brand partnerships dissolved, and boycott campaigns spread across every major platform. His career — built over years of steady work — was dismantled almost overnight.

Importantly, Phạm Thế Kỷ has never been found guilty of any crime related to Yu Menglong’s death. The legal system closed the file without charges. Yet in the eyes of a large segment of the public, legal closure means nothing when emotional closure has not been achieved. The internet became judge, jury, and executioner — delivering a sentence without parole, without appeal, and without end.

The case forces uncomfortable questions. When outrage spreads faster than facts, and when collective emotion can override due process, where does real justice live? Is a person entitled to the presumption of innocence only until the internet decides otherwise? And what happens when public opinion becomes more powerful than the law itself — when a hashtag can destroy a life more effectively than any verdict?

Phạm Thế Kỷ’s story is not unique, but its speed and scale make it particularly stark. In today’s digital landscape, reputations are fragile, and once branded guilty by the crowd, redemption becomes nearly impossible — even when the courts say otherwise. The “Good People” list was meant to honor virtue. Instead, this year it became a mirror reflecting one of the darkest truths of our time: in the age of instant connectivity, the mob can sometimes move faster — and hit harder — than justice ever could.

Leave a Reply